How to Compromise Like a Pro

We’ve all been stuck in an argument with our partner that we can’t resolve. It’s gridlock: neither of us can win and compromise doesn’t seem possible. When that happens, it’s easy to get frustrated, overwhelmed and unable to move the conversation forward.

With the Gottman Method, it’s possible to move out of these gridlocked conflicts into a solution that respects both partners’ core needs while discovering untapped possibilities for compromise. I will break it down for you using an example from my couples therapy practice.

Consider the case of Alicia and Cody, a real couple with a relatively common problem that they can’t seem to resolve (I’ve changed their names and demographics to protect their identities).

Alicia and Cody

Cody wants Alicia to go with him to a party this weekend. People energize him, but Alicia wants to curl up at home and watch a movie, just the two of them. It’s a familiar conflict to them, and they keep getting stuck in the same loop. It goes something like this.

A Gridlocked Conflict

Cody: “Come on, I’ve been so good staying at home with you. We haven’t been out in forever!”

Alicia: “Then just go out on your own. I’m not forcing you to stay home.”

Cody: [Rolls his eyes] “Oh sure, no pressure from you to stay home. Look, you’ll know people there. I really think you’ll have fun!”

Alicia: Sighs. “Jeez…okay! If that’s how you’re going to be like that, I’ll go!”

Cody: “Look, I want you to go, but only if you want to go.”

Alicia: “But I don’t want to go! You know parties stress me out.”

Cody: “OK, fine! We’ll do it your way… again!”

Alicia: “No, no, I’ve said I’ll go, and I will!”

At this point, it doesn’t matter if Cody and Alicia go out or stay home. Despite their desire to connect and have fun together, they’re stuck in a lose-lose situation.

If they go, Alicia will sulk and make sure Cody notices how unhappy she is. Resentful and guilty, Cody will do his best to ignore her.

If they stay home, they will ignore each other and do their own thing. Now it’s Alicia who will feel guilty and resentful and Cody who’s the martyr.

Why Can’t We Compromise?

Logically, a compromise solution should be straightforward. They should go out together sometimes and sometimes stay home. They would only need to figure out whose turn it is this time.

So why didn’t their attempts at compromise work? Why wasn’t it easy? If we look at their overall strategy, we can see why it failed.

A Lose-Lose Solution

The problem with Cody and Alicia ’s approach to compromise is that instead of encouraging collaboration it creates a stand-off. Each has their own sense of self-sacrifice and unfairness, and it dominates their approach.

Alicia is thinking, “It’s far more taxing for me to go out than it is for him to stay home. How is that fair? Whereas Cody is thinking “I ask for so little from her, and she won’t even relax enough to have a little fun with me?”

The problem is that both are too invested in trying to sway the other, and then when they were rebuffed they become too reactive to the other’s feelings. And the irony is that although neither wants the other to be unhappy – just the opposite – that’s exactly how it always ends.

Solvable vs Unsolvable Problems

To get traction with a conflict like this, Cody and Alicia need to understand the difference between solvable and unsolvable problems.

“According to the Gottman Institute, seventy percent of relationship conflict is caused by unsolvable problems.”

Unsolvable problems, also called perpetual problems, are rooted in fundamental differences between partners. Things like personality, values, and lifestyle preferences. Unlike solvable problems, which arise from specific circumstances and tend to be transient, unsolvable problems tend to cause the same conflict over and over because of the permanent underlying differences. In the case of Cody and Alicia, because he is an extrovert and she is an introvert, these traits are unlikely to change.

According to the Gottman Institute, seventy percent of relationship conflict is caused by unsolvable problems, so Cody and Alicia need to recategorize their conflict and take a different approach. Otherwise, they will gridlocked.

The nature of gridlock is that the underlying differences between partners remain hidden from view. Without bringing those differences to light, couples can remain indefinitely gridlocked in in a cycle of blame and bewilderment. Here’s how to get out of it.

Getting Cody and Alicia out of Gridlock

Because Cody and Alicia’s unsolvable problem is rooted in a common personality difference (introversion versus extroversion), to move out of gridlock they first have to realize that this personality difference is never going to go away. It’s baked into who they are as individuals, and as a result it’s baked into their relationship.

“In the Gottman world, we say that when you pick a partner, you pick a set of problems. ”

That’s a big one because there may be a sense of hopelessness when they realize that. But there may also be a sense of relief. They don’t have to blame each other anymore. It’s nobody’s fault.

In the Gottman world, we say that when you pick a partner, you pick a set of problems. If you had picked another partner, you’d have a different set of problems. But you didn’t. You picked this one, so it’s time to relax into those differences.

If each partner can deeply understand the other’s point of view, feelings, beliefs and dreams, then compromise is possible. Without understanding, we can never get to the heart of the conflict. But once we do, resentment and bitterness tend to drain from the issue. At that point it’s much easier to find new ways to compromise, because we are no longer trying to make the issue disappear, we are actively engaging with it as a permanent phenomenon.

The Gottman Method has two interventions for gridlocked conflicts. One is called Dreams Within Conflict, which you can read more about here. The other is called The Art of Compromise, which is described below.

The difference between the two is that Dreams Within Conflict is a deeper dive into the underlying aspects of each person’s experience, so it’s often used as step one with the Art of Compromise as step two. The Art of Compromise, on the other hand, can be used as a one-step process if the underlying issue is relatively straight-forward.

In this case, I chose to use the Art of Compromise with Cody and Alicia because it was a basic personality issue relatively uncomplicated by other factors, and both partners had a good grasp of its fundamentals.

Your Gottman therapist can guide you toward the best intervention for each gridlocked conflict.

“To make compromise work, we first have to decide what we can’t compromise on. ”

How to Compromise in Four Steps

The Gottman Method "Art of Compromise" exercise is a structured activity designed to help you practice the essential skills of compromise in a constructive and collaborative manner.

To make compromise work, we first have to decide what we can’t compromise on. This is so we won’t inadvertently accept a compromise that violates our core needs.

Note: this exercise is not meant to be used during a conflict . Rather, it’s meant to be done when both people are calm. Here’s how to do it.

Step 1: Identify You Core Needs

The first step in compromise is to identify your core needs. Compromise fails when one partner gives up too much.

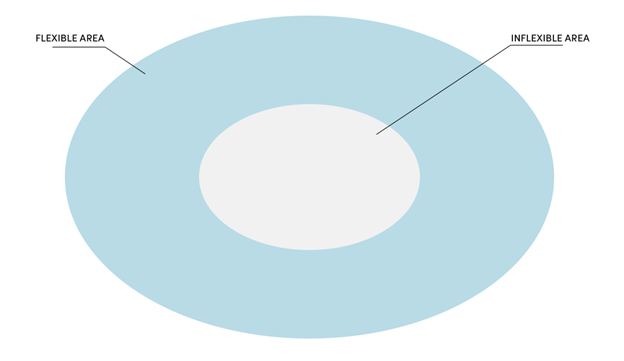

Fill in the smaller oval with your must-haves or non-starters. These are your inflexible areas. Try to keep this list short by including only one or two needs that are essential to your happiness.

Compromise Ovals

Alicia and Cody’s inflexible areas came out this way:

• Alicia: I need to limit the amount of time I spend with other people, or I feel drained, and I need to do fun things with my partner that don’t involve a big group of people.

• Cody: I need to socialize with friends at least once a week or I feel depressed, and I need you to come with me some of those times or else I feel like I don’t have a partner.

Step 2: Define Your Flexible Areas.

The next step is to define the areas in which you have more flexibility and write them in the larger oval. Try to make this list as long as possible. Think about all the ways you could find common ground with your partner, given what you know about them.

Alicia and Cody’s flexible areas came out this way:

Alicia

• It’s easier for me to socialize with people I know, so I would be open to more outings that don’t involve a lot of new people.

• Big groups tire me out more, so I would be open to more outings with smaller groups of people.

• Talking to people tires me out, so I would be more open to outings where there was an engaging activity rather than endless conversation.

• My fatigue increases with time, so I would be open to more outings that had a duration of three hours or less.

• I feel uncomfortable when I feel like I can’t escape a social situation, so I would be open to more social activities that took place at our house, where I could retreat if necessary.

Cody

• Since you work later than I do, I could get some of my social needs met by going out with work friends for an hour or two, maybe once a week.

• Since I would like to have you with me when we are with close friends, I can cultivate other groups of people socialize with on my own.

• I’m happy to go out by myself with our close friends occasionally. We just need to have a way to communicate why you’re not there that feels valid and comfortable to both of us.

• I would like to give you more time just the two of us, but if we could find a way to spend a portion of that time doing things out of the house, then I wouldn’t feel so claustrophobic when we do stay home.

Step 3: Talk about Your Answers

This step is about more deeply understanding your partner’s flexible and inflexible areas so that you can develop a compromise that will work for both of you. Take turns being the speaker and the listener and don’t switch roles until the speaker feels understood.

Ask clarifying questions. Be curious, and don’t try to respond with your own point of view until it’s your turn. Above all, don’t try to compromise until you’ve each asked each other all the following questions.

To move the conversation forward, you can ask your partner these questions:

• Help me understand why your inflexible area is so important to you.

• What are your core beliefs, feelings, or values about this issue?

• Help me understand your flexible areas.

• What do we agree about?

• What are our common goals?

• How might these goals be accomplished?

• How can we reach a temporary compromise?

• What feelings do we have in common?

• How can I help to meet your core needs?

For Alicia and Cody, the most important things they came to understand about each other were:

• They both wanted to spend time with each other, but not always in the same setting.

• Their ways of socializing were based primarily on feelings; a sense of excitement and belonging for Cody, and a sense of safety and fatigue for Alicia.

• They both wanted to spend time with others as well as have time alone, just in different proportions.

• They both wanted to accommodate their partner’s needs, especially if their own needs were also being met.

• They each had several compromise ideas that sounded good to the other.

Step 4: Develop a Temporary Compromise

Now work on coming up with a temporary compromise by discussing the questions below so that both you and your partner’s needs are included. Talk about what you can and cannot do on this issue in terms of honoring your partner’s needs right now.

For Alicia and Cody, their temporary compromise was to lean into the activities that supported them both: more solo socializing for Cody and more mutual socializing that supported Alicia’s needs.

Why temporary? Because it helps to evaluate the compromise after living with it for a while to see how it’s working and if anything needs to be adjusted.

What If Compromise Fails?

It’s worth noting that sometimes compromise isn’t possible. This can happen when one person’s dream is the other’s nightmare. For example, if one person’s inflexible need is to have children and their partner is inflexible about not having children, there is likely no compromise solution that will satisfy them both. In these cases, couples may need to let go of the relationship with a shared understanding of why they need to move on. For most couples, however, the Art of Compromise procedure help uncover a relatively large area where both partners’ needs can be at least partially met.

Yield to Win

For a compromise to truly work, it helps to adopt the Aikido principle “yield to win.” The idea is that direct opposition, with two forces opposed, is a big mistake.

The essence of yield to win lies in the recognition that resistance often leads to conflict and escalation, while yielding allows for fluidity, adaptability, and ultimately, victory. By embracing the principle of yielding, Aikido practitioners cultivate a mindset of non-aggression and cooperation, seeking to resolve conflicts peacefully and without harm to themselves or others. In this way, "yield to win" extends beyond the physical techniques of Aikido to encompass a broader philosophy of harmony, resilience, and mutual respect in all aspects of life.

If you would like more information on how to apply these concepts to your situation, schedule a free consultation.